Over the past decade, the United States and Russia, the two countries holding 90 percent of the world’s nuclear weapons, have withdrawn from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty and the Open Skies Treaty, while the New START treaty — the last remaining bilateral agreement limiting their nuclear arsenals — has a fast-approaching expiration date. Instead of reducing the size of their arsenals, China and North Korea are building up their stockpiles while the United States, Russia and China are all implementing nuclear modernization plans. The old guardrails to great power competition have rusted away, leaving few risk reduction measures in place to manage competition over geopolitical hotspots like Taiwan and Ukraine.

It is within this context that the the Department of Physics at the University of Maryland convened a panel on “The Future of Nuclear Deterrence and Arms Control,” to discuss the troubling state of affairs and assess how to reduce the risk of nuclear catastrophe.

The event featured a panel – moderated by Susan Eisenhower, an author and expert on international security, space policy, and U.S. - Russian relations – of esteemed nuclear physicists including Frank N. von Hippel, a Senior Research Physicist and Professor of Public and International Affairs Emeritus with Princeton’s Program on Science & Global Security; Roald Sagdeev, former head of the Soviet space agency IKI and advisor to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev; John Holdren, former Director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and Senior Advisor to President Obama on science and technology from 2009-17; and Richard Garwin, IBM Fellow Emeritus at the Thomas J. Watson Research Center.

Nancy Gallagher, the director of the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland (CISSM), offered opening remarks that summarized the dilemma facing current policy makers, “...the news today is full of reasons to worry and wonder whether we need more tailored nuclear options to deter or defeat all possible nuclear-armed adversaries that we face today or if we need to invest more heavily in arms control, nonproliferation, and other forms of cooperative nuclear risk reduction.”

Some believe that the United States will need enough nuclear weapons to deter Russia and China simultaneously in different arenas. Others argue that this logic inevitably leads to the U.S. fielding new and possibly more nuclear weapons, which would drive the threat perceptions of Moscow and Beijing and likely instigate a reaction, and eventually, an arms race. Nuclear threats have been a key dimension of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and tensions between the nuclear powers are high, but Gallagher argued that the world has experienced similarly high tensions before. Calamity is not predestined, and leaders have found ways in the past to reduce the risk of nuclear conflict.

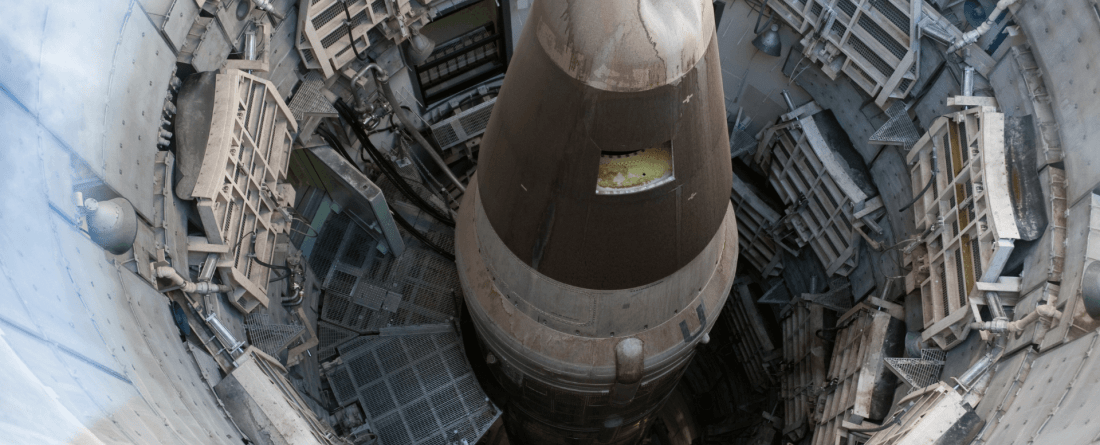

During the panel discussion, von Hippel argued that nuclear deterrence is now obsolete. He stressed that the United States has a dangerous “use it or lose it” mentality when it comes to its intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). By keeping them in a launch-on-warning posture, the United States is signaling it will launch its nuclear weapons if it believes that another country has authorized a first strike. von Hippel believes this is misguided. He posited that the United States’ experience in Ukraine means it can and should rely on its conventional weapons for war and to deter aggression.

Sagdeev reminded the panel and the audience of the unique role played by his fellow nuclear physicists. By cracking the code and splitting the atom, physicists have a special responsibility to help manage the use of nuclear technology. Not only have nuclear physicists been deeply involved in the technical arms control negotiations, but the science diplomacy these physicists engaged in outside of government often laid the groundwork for government-to-government contact between the great powers. While the current geopolitical climate is grim, Sagdeev hoped that the meeting between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky was an opening to get the United States and Russia back on the right track.

Garwin highlighted Russian President Vladimir Putin’s lack of respect for international norms and the rule of law as the greatest threat to global peace and security. He expressed concern about a potential demonstration test by Russia and cautioned against the United States responding with its own nuclear test, which would severely undermine a key international norm against such activities.

Despite significant challenges, Holdren took the opportunity to discuss what the United States can do about it. He argued that the United States could declare that it will never use nuclear weapons in response to conventional, biological, or other types of attacks. The United States could also impose a “no first use” policy, which might also lead to the removal of ICBMs from their alert posture, eliminate silo-based ICBMs, and revise the rules on the command of nuclear weapons. Other potential de-escalatory steps include signing the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, engaging with Russia in strategic and non-strategic nuclear weapons reductions, and pushing for a global prohibition of nuclear weapons.

Outside of government, scientists and civil society help to shift the debate toward finding new cooperative mechanisms to reduce the risk of nuclear annihilation. At CISSM, Gallagher and CISSM senior fellow, Steve Fetter, are researching new paradigms for adversaries to build more constructive, cooperative international security relationships. Catastrophic accidents have been narrowly avoided time and time again throughout the Cold War, but the law of odds suggests the world cannot count on being so lucky in the future. In the closing words of John Holdren, it is time to reduce nuclear tensions and “get on with the business of getting rid of nuclear weapons.”

Original news story published by the School of Public Policy