While a doctoral student researching Black performance and the civil rights movement, Assistant Professor of English Julius Fleming, Jr. discovered a newspaper article about a 1964 performance of Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” in the Mississippi Delta. At this performance, the article notes, was acclaimed civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer, who connected the play's plot line—two characters waiting for a person who never comes—to Black Americans' perpetual wait for freedom. “We know something about waiting,” Hamer declared during the intermission.

Fleming began to notice the theme of waiting—and Black people’s resistance to it—throughout the Black theater archives he was visiting, in scripts, reviews, diaries and more. While prominent cultural and political figures like William Faulkner, Dwight Eisenhower and Robert Kennedy urged black people to “wait” and to “go slow” in their fight for civil rights, Fleming noticed how Black theater often energized the demand for “freedom now” that became a hallmark of the civil rights movement. For instance, Langston Hughes’ 1964 play “Jericho-Jim Crow” featured Black activists who resisted white characters’ demands that they be patient and traced those demands back to slavery.

After more than a decade of research, Fleming’s new book, “Black Patience: Performance, Civil Rights, and the Unfinished Project of Emancipation,” suggests that Black theater—including lesser-known plays and unexpected spaces where these plays were produced—boldly reinforced the clarion call for “freedom now” expressed by civil rights activists like Hamer, Martin Luther King, Jr. and John Lewis. He also illuminates how the demand to wait for freedom continues to undermine the modern-day fight for freedom, from instances of police violence to restricted access to voting rights.

On April 25, the English Department will host a virtual book talk of “Black Patience” featuring Distinguished University Professor Emerita Mary Helen Washington. Ahead of the event we spoke with Fleming about theater, waiting and Black resistance.

Many people may not think of or understand theater to be a tool used during the civil rights movement. What can theater help us understand about the movement?

Much of the scholarship around the civil rights movement is focused on photography and television, so part of what I was interested in during my dissertation was the importance of theater to the civil rights movement as an artistic form. So, I went to the archive to learn more—to Chicago, Atlanta, New Orleans, Jackson, New Haven, New York City and even Amsterdam. And over time I began to recognize that Black people were saying through theater: “We don't want to wait for freedom … we want our freedom now.” A part of what was so useful about civil rights theater is that it could travel, and it allowed for the assembly of audiences who could experience collectively these theatrical challenges to the racial project of Black patience. And there were often talkbacks after the play that helped to further facilitate community and dialogue and often ignited shifts in Black political consciousness and civic participation.

You argue that time has been used as a weapon of oppression toward Black people, asking them to wait for their freedom.

Duke Ellington wrote a play in 1963 to celebrate 100 years of emancipation called “My People.” This play was a part of an international exhibition in Chicago that celebrated the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation—or 100 years of legal freedom from U.S. chattel slavery for Black folks. And yet, Ellington shows how Black people were still waiting for freedom. The play, a musical, captures how even as Black people have served as military heroes in the Spanish American War or have essentially built the United States through their manual labors, they were still demanded to wait for their freedom a century after emancipation.

Waiting was not just a tool of oppression, though. During the civil rights movement, Black activists started to transform time from a weapon of anti-Black oppression into an instrument of social and political change. For instance, in the book I write about sit-ins and jail-ins—forms of embodied political protest in which activists said: “Hey, arrest me. I'm not going to pay bail. I’ll do my six months in prison because my waiting in prison will bring more attention to the problem of anti-black racial violence.” In this sense, the jail-in and the sit-in are radical embodied experiments in and with time. They function as insurgent performances of waiting that turn the logic of Black patience on its head.

Can you talk about the way noted civil rights activist and artist James Baldwin used theater to explore time?

During the civil rights movement, Baldwin wrote the play “Blues for Mister Charlie,” which opened on Broadway in 1964. The plot suggests that the answer to solving the race problem lies not in the habit of looking at or studying Black people, but in more closely examining white people, or “Mr. Charlie,” whom Baldwin sees as the source of modernity’s racial problem.

During the civil rights movement, there were hundreds of photographic and televisual images of Black people being bitten by dogs, or sprayed with fire hoses, for instance. These images were intended, in many ways, to produce empathy among viewing audiences and thereby to hopefully ignite structural change in the racial fabric of the modern world.

But many white audience members did not like having to sit patiently through a play where they are rendered as racial antagonists. Interestingly, their discomfort with these racial images of self was often couched in complaints about the play’s aesthetics or its “long” running time. From New York to London, this play and its live performances revealed how, at the same time that white people were demanding Black patience, they exhibited a profound degree of what I call in the book “white impatience,” an ironic absence of patience among white people.

How does the narrative of waiting still show up through theater today?

During the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 there was a production of “Waiting for Godot” staged in New Orleans. The production’s message was clear: Why did Black people have to wait so long for assistance from the federal government? Why were they forced to climb onto their roofs with “SOS” and “save us” signs while the affluent white neighborhoods were assisted first?

Another example is the University of Chicago's trauma center, which was closed down in 1988 because (according to activists) there were so many gunshot wound victims and unpaid bills that the hospital started to lose money. This closure meant that people on the south side of Chicago—a historically Black region of the city—who suffered heart attacks or strokes would have to wait for medical care as they endured a now longer ride to the nearest hospital, which was sometimes more than 40 minutes away. A group of activists started mounting performances of activism outside of the hospital, staging “die-ins” and drawing chalk outlines around their bodies to bring awareness to this problem.

So, whether you think about access to federal aid or medical care, waiting and patience continue to pose a threat to Black people and to Black life. And yet, Black people continue to resist Black patience and to transform its logics into strategies of Black political possibility and Black world making.

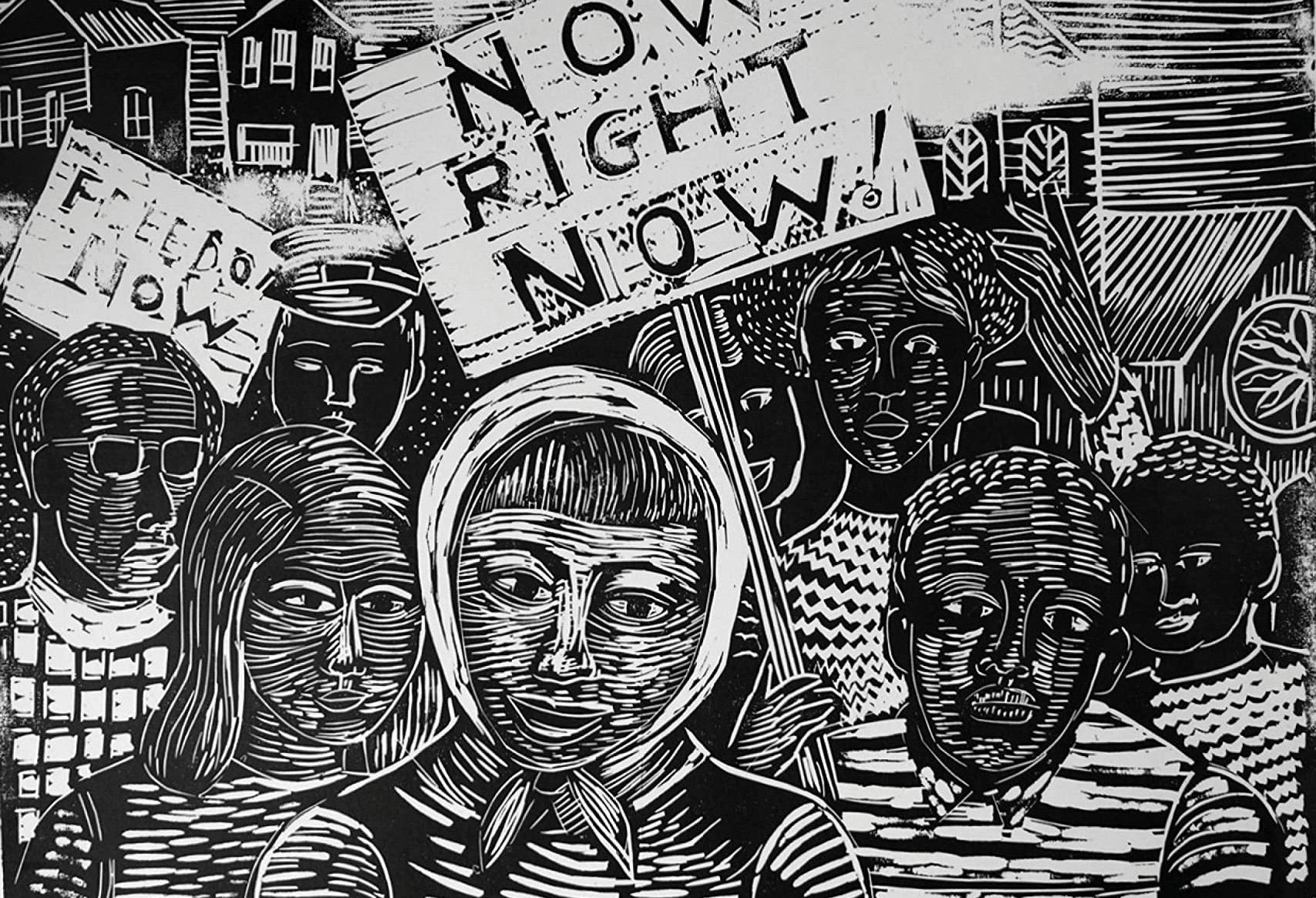

Image credit: Monotone linocut of artist Margaret Burroughs' work "Now Right Now."

Original news story written by Rosie Grant